Reposting in full. This is good stuff here!

Reposting in full. This is good stuff here!

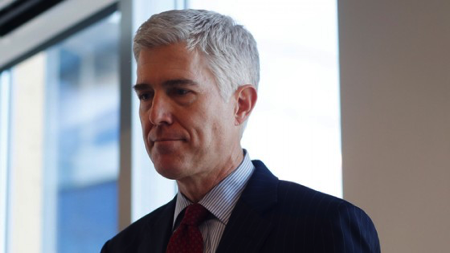

President Donald Trump announced tonight that he will nominate Honorable Neil M. Gorsuch (a 49-year-old judge in the Tenth Circuit of the United States Court of Appeals) as a Justice on the Supreme Court, replacing the recently deceased Justice Antonin Scalia (1936-2016).

On April 7, 2016, Gorsuch delivered the 2016 Sumner Carnary Memorial Lecture at Case Western Reserve University School of Law, entitled “Of Lions and Bears, Judges and Legislators, and the Legacy of Justice Scalia.” It was later published in the Case Western Reserve Law Review66, no. 4 (2016): 905-20.

The lecture, as the title suggests, considers the legacy of Justice Scalia, whom he says, “was a lion of the law: docile in private life but a ferocious fighter when at work, with a roar that could echo for miles.”

Even though “Volumes rightly will be written about [Scalia’s contributions to American law, on the bench and off,” Gorsuch believes that perhaps the great project of his career was to remind us of the differences between judges and legislators.

To remind us that legislators may appeal to their own moral convictions and to claims about social utility to reshape the law as they think it should be in the future.

But that judges should do none of these things in a democratic society. That judges should instead strive (if humanly and so imperfectly) to apply the law as it is, focusing backward, not forward, and looking to text, structure, and history to decide what a reasonable reader at the time of the events in question would have understood the law to be—not to decide cases based on their own moral convictions or the policy consequences they believe might serve society best.

As Justice Scalia put it, “[i]f you’re going to be a good and faithful judge, you have to resign yourself to the fact that you’re not always going to like the conclusions you reach. If you like them all the time, you’re probably doing something wrong.”

Gorsuch writes:

It seems to me an assiduous focus on text, structure, and history is essential to the proper exercise of the judicial function. That, yes, judges should be in the business of declaring what the law is using the traditional tools of interpretation, rather than pronouncing the law as they might wish it to be in light of their own political views, always with an eye on the outcome, and engaged perhaps in some Benthamite calculation of pleasures and pains along the way.

Though the critics are loud and the temptations to join them may be many, mark me down too as a believer that the traditional account of the judicial role Justice Scalia defended will endure.

He offers three reasons for holding to this traditional view.

1. The Constitution

Judges, after all, must do more than merely consider it. They take an oath to uphold it. So any theory of judging (in this country at least) must be measured against that foundational duty. Yet it seems to me those who would have judges behave like legislators, imposing their moral convictions and utility calculi on others, face an uphill battle when it comes to reconciling their judicial philosophy with our founding document.

2. The separation of legislative and judicial powers

To the founders, the legislative and judicial powers were distinct by nature and their separation was among the most important liberty-protecting devices of the constitutional design, an independent right of the people essential to the preservation of all other rights later enumerated in the Constitution and its amendments. . . . [R]ecognizing, defending, and yes policing, the legislative-judicial divide is critical to preserving other constitutional values like due process, equal protection, and the guarantee of a republican form of government.

3. The lack of a viable alternative.

Consider a story Justice Scalia loved to tell. Imagine two men walking in the woods who happen upon an angry bear. They start running for their lives. But the bear is quickly gaining on them. One man yells to the other, “We’ll never be able to outrun this bear!” The other replies calmly, “I don’t have to outrun the bear, I just have to outrun you.” As Justice Scalia explained, just because the traditional view of judging may not yield a single right answer in all hard cases doesn’t mean we should or must abandon it. The real question is whether the critics can offer anything better. About that, I have my doubts.

He closes his lecture by explaining to his listeners that this traditional account of law and judging not only makes the most sense to him intellectually, but also fits with his own lived experience in the law.

My days and years in our shared professional trenches have taught me that the law bears its own distinctive structure, language, coherence, and integrity. When I was a lawyer and my young daughter asked me what lawyers do, the best I could come up with was to say that lawyers help people solve their problems. As simple as it is, I still think that’s about right. Lawyers take on their clients’ problems as their own; they worry and lose sleep over them; they struggle mightily to solve them. They do so with a respect for and in light of the law as it is, seeking to make judgments about the future based on a set of reasonably stable existing rules. That is not politics by another name: that is the ancient and honorable practice of law.

Now as I judge I see too that donning a black robe means something—and not just that I can hide the coffee stains on my shirts. We wear robes—honest, unadorned, black polyester robes that we (yes) are expected to buy for ourselves at the local uniform supply store—as a reminder of what’s expected of us when we go about our business: what Burke called the “cold neutrality of an impartial judge.”

Throughout my decade on the bench, I have watched my colleagues strive day in and day out to do just as Socrates said we should—to hear courteously, answer wisely, consider soberly, and decide impartially.

Men and women who do not thrust themselves into the limelight but who tend patiently and usually quite obscurely to the great promise of our legal system—the promise that all litigants, rich or poor, mighty or meek, will receive equal protection under the law and due process for their grievances.

Judges who assiduously seek to avoid the temptation to secure results they prefer.

And who do, in fact, regularly issue judgments with which they disagree as a matter of policy—all because they think that’s what the law fairly demands.

Justice Scalia’s defense of this traditional understanding of our professional calling is a legacy every person in this room has now inherited.

The entire piece is worth a read.

Via Justin Taylor