A new study released earlier this month in the journal Depression Research and Treatment contributes to mounting evidence against the “no differences” thesis about the children of same-sex households, mere months after media sources prematurely—and mistakenly—proclaimed the science settled.

One of the most compelling aspects of this new study is that it is longitudinal, evaluating the same people over a long period of time. Indeed, its data source—the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health—is one of the most impressive, thorough, and expensive survey research efforts still ongoing. This study is not the first to make use of the “Add Health” data to test the “no differences” thesis. But it’s the first to come to different conclusions, for several reasons. One of those is its longitudinal aspect. Some problems only emerge over time.

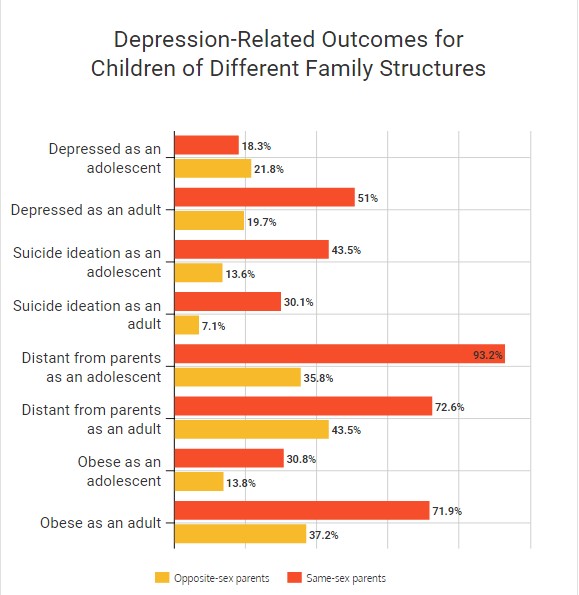

Professor Paul Sullins, the study’s author, found that during adolescence the children of same-sex parents reported marginally less depression than the children of opposite-sex parents. But by the time the survey was in its fourth wave—when the kids had become young adults between the ages of 24 and 32—their experiences had reversed. Indeed, dramatically so: over half of the young-adult children of same-sex parents report ongoing depression, a surge of 33 percentage points (from 18 to 51 percent of the total). Meanwhile, depression among the young-adult children of opposite-sex parents had declined from 22 percent of them down to just under 20 percent.

A few other findings are worth mentioning as well. Obesity surged among both groups, but the differences became significant over time, with 31 percent obesity among young-adult children of opposite-sex parents, well below the 72 percent of those from same-sex households. While fewer young-adult children of same-sex parents felt “distant from one or both parents” as young adults than they did as teens, the levels are still sky-high at 73 percent (down from 93 percent during adolescence). Feelings of distance among the young-adult children of opposite-sex parents actually increased, but they started at a lower level (from 36 percent in adolescence to 44 percent in young adulthood).

To be fair, life in mom-and-pop households is not simply harmonious by definition. It is, however, a recognition that it is not just stability that matters (though it most certainly does). It’s also about biology, love, sexual difference, and modeling.

Additionally, more kids of same-sex parents said “a parent or caregiver had “slapped, hit or kicked you,” said “things that hurt your feelings or made you feel you were not wanted or loved,” or “touched you in a sexual way, forced you to touch him or her in a sexual way, or forced you to have sex relations.” In fairness, this is a grouping of traumatic events that strikes me as unbalanced, what with the rather profound difference between hurt feelings and molestation. A follow-up inquiry revealed very few reports of the latter among Wave IV respondents.