When I was 13, I visited my brother and his family in Denver. One of the most vivid memories was the endless gas lines. We would drive from station to station, only to find “out of gas” signs or lines stretching for a mile. Even after waiting in a gas line, you might reach the front only to discover they’d just run out.

When I was 13, I visited my brother and his family in Denver. One of the most vivid memories was the endless gas lines. We would drive from station to station, only to find “out of gas” signs or lines stretching for a mile. Even after waiting in a gas line, you might reach the front only to discover they’d just run out.

At 13, I didn’t understand what caused the gas shortages. The news blamed OPEC, claiming they cut back on oil production. But my brother, a CPA, explained that the real culprit was President Nixon’s price controls on gas. He told me that when gas prices are set below the going rate, shortages are bound to happen.

There’s an old joke: A guy pulls up to a Shell station and asks, “How much is your gas per gallon?” The attendant replies, “75 cents a gallon.” The guy says, “75 cents? I can get it across the street at Esso for 60 cents a gallon.” The attendant shrugs and says, “Well, then why don’t you fill up there?” The guy replies, “Well, they’re out of gas.” The attendant smiles and says, “When we’re out of gas, we only charge 50 cents a gallon.”

Fast forward to my junior year of college. I had the opportunity to travel behind the Iron Curtain to the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) and Czechoslovakia, visiting East Berlin, Leipzig, Dresden, and Prague.

Some memories from that trip are still vivid: grocery stores with sparse food options and empty shelves. Socialism replaced Adam Smith’s “Invisible Hand” of the free market with state control. The more consistently socialism is practiced, the worse the outcomes: starvation, loss of liberty, and violence against citizens aren’t accidents—they’re inherent to the system.

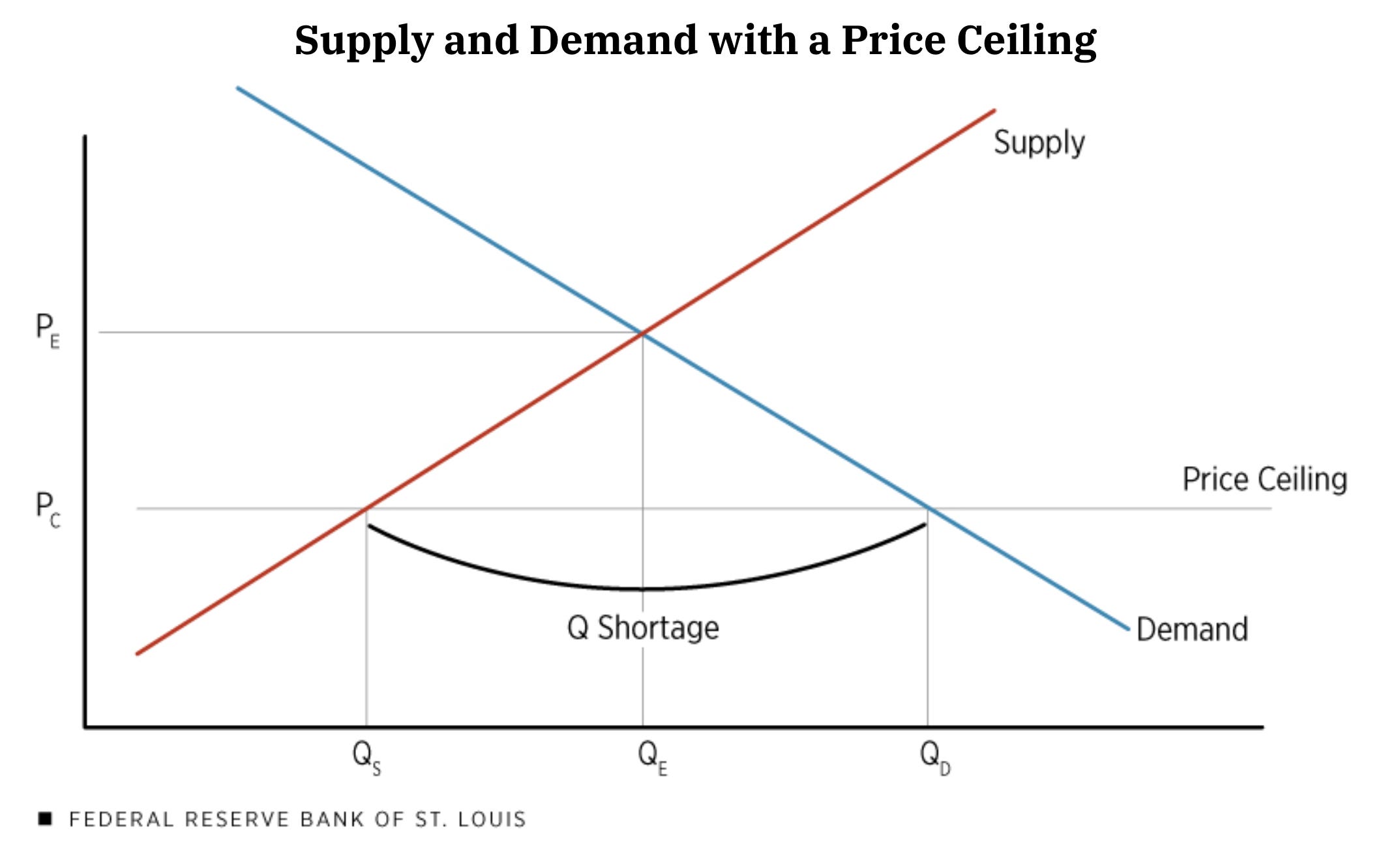

When I took economics in college, it was a wake-up call. I learned how governments, in hopes of making things “affordable,” often set a ‘price ceiling’ below market equilibrium. But just as it can’t ban gravity, the government can’t ban the Law of Supply and Demand.

When I took economics in college, it was a wake-up call. I learned how governments, in hopes of making things “affordable,” often set a ‘price ceiling’ below market equilibrium. But just as it can’t ban gravity, the government can’t ban the Law of Supply and Demand.

The most immediate impact of price ceilings is a string of shortages. Artificially low prices boost demand while discouraging supply, leading to scarcity. Sellers often respond by cutting corners to stay profitable, resulting in a decline in quality. Shrinkflation is a common tactic, reducing the size of a product – like putting fewer chips in each bag – while keeping the price the same as before.

When prices are unable to balance the market, rationing becomes inevitable. Goods may be rationed through first-come/first-served systems, explicit rationing, or even corruption. These methods benefit the resourceful or well-connected, not those most in need, increasing social waste and undermining the fairness that price controls are supposed to ensure. During the 1970s gas shortage, for example, wealthy Americans paid others to wait in line for gas for them.

But for over 46 centuries, governments have tried price controls, always leading to the same disastrous results: widespread shortages, black markets, and economic collapse. As far back as 2830 B.C., in Egypt’s Fifth Dynasty, Monarch Henku boasted of his control over grain, reflecting early attempts at regulating food supplies. From ancient Egypt to the Roman Empire and the Soviet Union, price ceilings consistently caused goods to vanish from shelves and made basic necessities scarce or inaccessible.

Which brings me to Kamala Harris’ newest harebrained scheme of pushing for food price controls. Ironically, Bidenomics created the price inflation she now wants to “protect” us from. But now, Harris threatens to punish grocery stores for charging more than their costs. Grocery stores only make one to two pennies on the dollar—meaning, they have to pass along costs that come straight from the money printers.

But not all grocery stores are created equal. Walmart can subsidize its groceries by using the rest of its business. Small and low-income stores lack those economies of scale and are the first to go out of business.

So how do you protect the grocery stores from going out of business? You have to freeze costs on food producers (Tyson, Kraft, General Mills, etc.) as well. But they have suppliers too, so their suppliers’ costs must also be frozen.

Harris fails again and again to think past the face value of her scattered ideas, and refuses to trust the market’s ability to balance itself effectively. But the lesson is clear: price controls do not solve problems – they create them. By distorting the market, these failed economic experiments will ultimately lead to shortages, inefficiency, and greater hardships in the daily lives of those they claim to protect.