Taking on the insanity plea and how it affects us locally in the Pacific Northwest. This editorial ran in today’s Moscow-Pullman Daily News.

The Moscow-Pullman Daily News reports that Jamie Carosino, a woman involved in gunfire aimed at her boyfriend and his parents, was found not guilty by reason of insanity. Last month, Carosino engaged the Whitman County SWAT in a tense standoff after allegedly discharging her boyfriend’s 9mm handgun at him. According to court records, this startling ordeal occurred after her partner requested that she vacate his residence, sparking a frenzy that kept local residents on high alert.

The situation escalated when, not long afterward, Carosino purportedly brandished her boyfriend’s AR-15 and fired a round at his parents’ car. Hours of negotiation with SWAT followed while Carosino refused to leave the house, and a search of the premises and her car revealed a cache of firearms, ammunition, drugs, and even a pair of brass knuckles.

Whitman County Superior Court found Carosino criminally insane, and Judge Gary Libey dropped the felony assault charges against her. Instead, he ordered her committed to the Eastern State Hospital in Medical Lake, Washington, for treatment.

Whitman County Superior Court found Carosino criminally insane, and Judge Gary Libey dropped the felony assault charges against her. Instead, he ordered her committed to the Eastern State Hospital in Medical Lake, Washington, for treatment.

I am no fan of the insanity plea. It blurs the line between evaluating guilt and meting out punishment. A trial consists of two distinct phases: the ‘adjudicating responsibility’ phase, when the court determines whether the defendant committed the crime, and the ‘dispensing justice’ phase, which determines the appropriate punishment after conviction.

The former hinges on establishing the defendant’s factual guilt beyond reasonable doubt (did they perform the act?) and legal guilt (did the act fulfill the constituents of the charged offense?). The latter considers factors like the severity of the crime, the defendant’s criminal history, victim impact, and mitigating aspects such as mental health or personal circumstances.

The insanity defense is by nature easily manipulated. Think Corporal Klinger’s attempts for a Section 8 discharge from the Army in “MASH”; a claim of insanity is a convenient excuse that cannot be entirely disproved. Assessing mental health and the defendant’s mental state during the act is a subjective, labyrinthine task that is outside the capacity of a layperson in the jury.

The insanity defense also redirects the spotlight from where it truly belongs—on the victims of the crime. It obsesses over the perpetrator’s mental state rather than the victims’ plight and their quest for justice.

Lastly, the base line should be that all individuals are held responsible for their actions, mental health compromised or not. In our finite system of justice, mental disease ought to mean more responsibility of reparations on the criminal during the fallout of a crime, not less. Yet as Thomas Sowell notes, “We seem to be getting closer and closer to a situation where nobody is responsible for what they did but we are all responsible for what somebody else did.”

Both alcoholism (Alcohol Use Disorder) and drug addiction (Substance Use Disorder) are categorized as mental diseases. But when a schizophrenic goes off his antipsychotics and commits a crime, that’s a valid insanity plea. When a drunk or druggie commits a crime under the influence, why can’t they plead not guilty by reason of mental disease? Perhaps that is in the works under our evolving legal system.

Despite Washington State’s acceptance of the insanity plea, Idaho eliminated it in 1982. The U.S. Supreme Court in Clark v. Arizona (2006) confirmed the constitutionality of a state to restrict or abolish the insanity defense, and Idaho’s position holds firm: offenders should receive the punitive consequences of their behavior.

Despite Washington State’s acceptance of the insanity plea, Idaho eliminated it in 1982. The U.S. Supreme Court in Clark v. Arizona (2006) confirmed the constitutionality of a state to restrict or abolish the insanity defense, and Idaho’s position holds firm: offenders should receive the punitive consequences of their behavior.

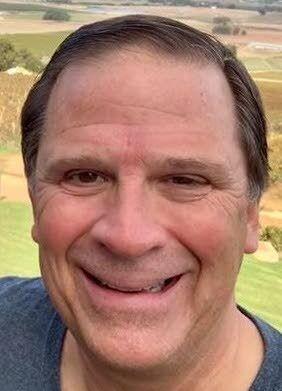

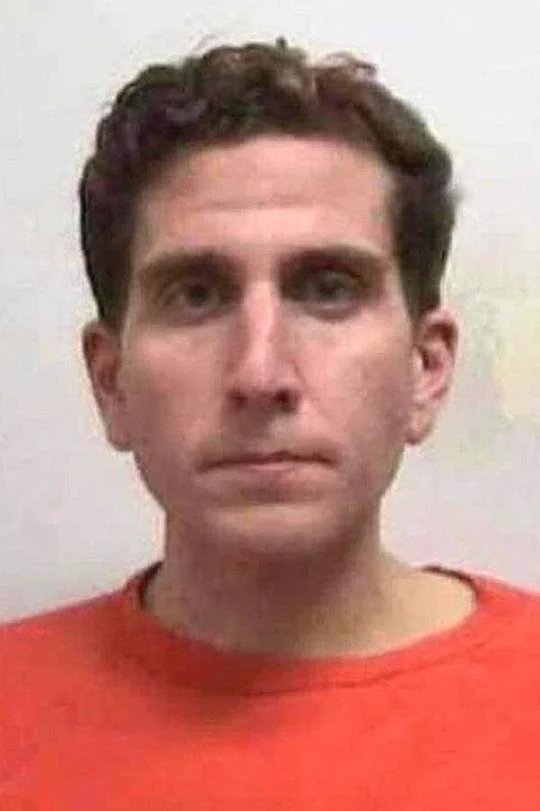

This becomes even more poignant as we approach Bryan Kohberger’s upcoming Moscow trial. Unlike Carosino, Kohberger’s defense team won’t have the luxury of pulling an insanity defense. If Kohberger is indeed found guilty, Idaho can mete out true justice for the stabbing deaths of the four University of Idaho students.

The Biblical principle “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth” (Ex. 21:24, Lev. 24:20, Deut. 19:21) identifies a structured approach to justice, demanding fitting recompense and reprisal. Translated into legal parlance, we arrive at the Latin phrase ‘lex talionis,’ underscoring the principle that the punishment should match the crime’s severity. In the event Kohberger is convicted of the quadruple murders, it’s too bad that he can only be put to death once for four lives that were brutally slaughtered.