A fascinating article about how an Ancient Greek historian’s predictions directly relate to us today. And they should, since our system of government is based on the Greek’s republic.

A fascinating article about how an Ancient Greek historian’s predictions directly relate to us today. And they should, since our system of government is based on the Greek’s republic.

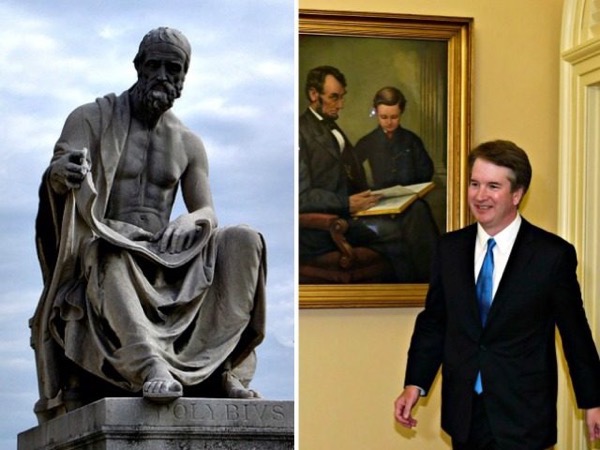

In particular, we might look to the Greek historian Polybius. He can’t directly address the current state of affairs, since he died in 118 B.C., and yet his wisdom still speaks to us, loud and clear. In fact, his analysis of political events during polarizing times is timeless.

One of his key themes was the way in which societies transition from one system to another. For instance, how is it that a democratic system falls apart, to be replaced by another kind of system—a worse system?

Mindful of the history of the ancient Greek and Roman republics, Polybius observed that a successful democracy had to observe certain groundrules to guide popular participation. That is, a democracy had to be more than just majority rule; if it was just that, it would prove to be unstable and short-lived. In his view, simple majoritarianism wasn’t democracy at all; it was, instead, to use another Greek word, an ochlocracy. That is, mob rule. (Interestingly, the Latin translation of “ochlocracy” was mobile vulgus, from which we get the word “mob.”)

This distinction, between democracy and mob rule, is critical. In The Histories, Polybius noted, “It is not enough to constitute a democracy that the whole crowd of citizens should have the right to do whatever they wish or propose.” Instead, he argues, a successful democracy requires “traditional and habitual” virtues of self-restraint, including “reverence to the gods, succour of parents, respect to elders, obedience to laws.” Only in such a disciplined context, he continued, can majority rule succeed. Indeed, only then “we may speak of the form of government as a democracy.”

In other words, for a democracy to flourish, certain preconditions have to be met, including a basic cultural commitment to deliberation and restraint. If this sounds “conservative” to the modern ear, well, so be it, although we can note that Polybius mades no prescription as to, say, tax rates, trade laws, or foreign policy. He was simply laying down the societal predicates for an effective democracy. And if that sounds conservative, well, it’s the conservatism of prudence and moderation, not conservatism bound to any larger ideology.

Importantly, the American Founders agreed with Polybius; indeed, they specifically reliedon him as an intellectual guide. For instance, James Madison, author of the U.S. Constitution, cited Polybius in a letter to Thomas Jefferson in 1787, and again in Number 63 of the Federalist Papers, published the following year. (The Federalist Papers, of course, were the articles and pamphlets written in support of the ratification of the Constitution.)

I encourage you to read the whole thing.