And Latah County even more so. From the Spokesman Review:

And Latah County even more so. From the Spokesman Review:

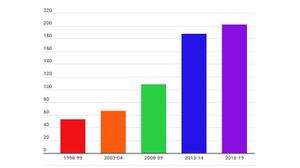

Idaho school districts will collect a record $202.2 million in voter-approved supplemental property tax levies this year.

This is the first time the supplemental levy bill exceeded the $200 million mark. A year ago, Idaho schools collected $194.7 million – a short-lived record.

Districts can and do use supplemental levies for a variety of purposes – including teacher salaries and benefits, classroom technology and textbooks. And many school officials say the one- to two-year levies are no longer supplemental, but instead help pay for essentials.

Idaho’s supplemental tax bill has nearly doubled over the past decade. The levies are a fact of life in districts large and small – from Coeur d’Alene, which will collect $16 million this year, to Mackay, which will collect $75,000.

All told, 93 of Idaho’s 115 school districts have a supplemental levy on the books, a number that has remained virtually unchanged for the past five years.

But while the vast majority of school districts continue to rely on extra help from local taxpayers, the picture of school funding is blurry. A legislative committee has recommended an overhaul of Idaho’s school funding formula – a complicated rewrite that figures to be one of the hottest issues in the 2019 legislative session. Under the latest version of the new formula, endorsed Monday by the committee, 36 districts and charters stand to receive fewer dollars from the state.

If lawmakers change the way the state carves up its education budget – which is by no means a sure thing – this could affect local tax bills.

Many district leaders “hate having to rely” on short-term local levies, said Rob Winslow, executive director of the Idaho Association of School Administrators. The “winners” – districts that receive more state funding under a new formula – could simply let their local levies expire. But by the same token, districts that lose state funding could need levies more than ever.

Moscow doesn’t have short-term levies but indefinite, infinitely long levies.

At least in the short run, Winslow doesn’t expect the supplemental levy picture to change much. “It’s all early,” he said Wednesday.

The rising supplemental levy bill illustrates shortcomings in Idaho’s K-12 budget, other education leaders said this week.

The $200 million pretty much mirrors the money districts and charters put into teacher salaries, supplementing the state’s salary line item, said Quinn Perry, the Idaho School Boards Association’s policy and government affairs director. The ISBA, the IASA and the Idaho Education Association want lawmakers to leave the state’s teacher salary budget line item intact, rather than folding that money into a new funding formula.

Revamping the funding formula won’t go far enough, IEA President Kari Overall said Wednesday. The state needs to back that up with a five- to 10-year plan to invest in schools.

“The $202.2 million in supplemental levies clearly illustrates what we have long understood – Idaho’s schools receive insufficient funding from the state,” she said. “Districts increasingly must rely on additional funding from local taxpayers to ensure basic programs are provided for Idaho students.”

State superintendent Sherri Ybarra takes a different view. She was appointed to work with legislators on the funding formula rewrite. Through a spokesman, Scott Phillips, Ybarra said the committee worked diligently on the new formula. She also repeated a refrain from her fall re-election campaign – pointing out that the state has increased K-12 spending by $100 million a year over the past four years.

“These are good signs, encouraging signs and certainly a step in the right direction,” Phillips said Thursday.

Like Ybarra, State Board of Education President Linda Clark served on the funding formula committee. Clark points out that the state’s growing reliance on supplemental levies has been a long time coming – going back to 2006, when lawmakers and then-Gov. Jim Risch shifted more than $200 million of school funding onto the state’s sales tax. That shift didn’t fully cover a cut in local funding, and it forced numerous districts to go to voters for help.

Clark sees some hope in the funding formula rewrite.

“Perhaps over time the new formula may relieve some of the pressure on local taxpayers to provide stopgap funding for school maintenance and operations,” she said.